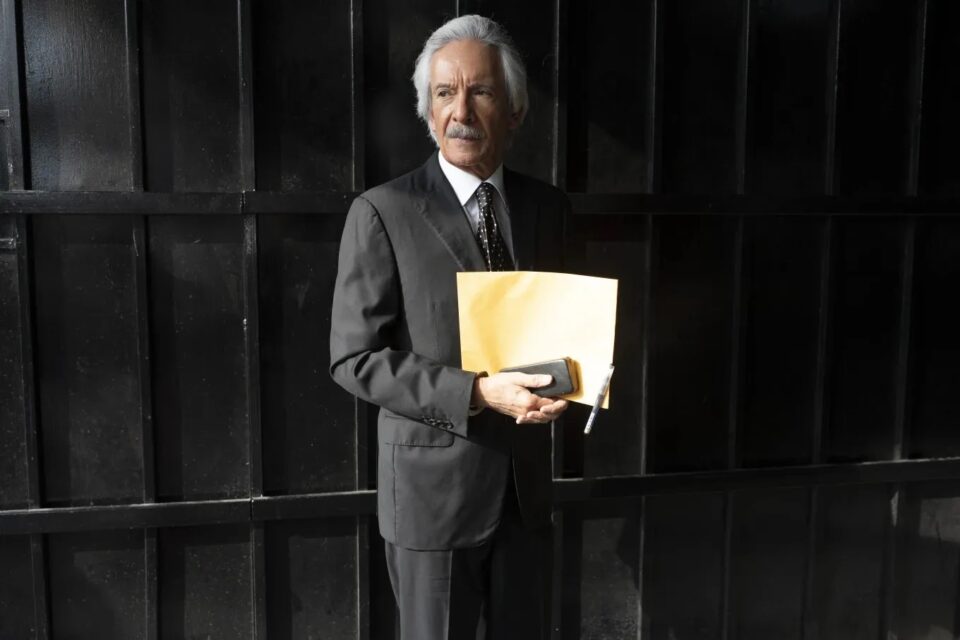

Earlier this year, CPJ went to Guatemala to advocate for journalist José Rubén Zamora’s release from prison. While there, we met with newly elected Guatemalan President Bernardo Arévalo and discussed opportunities for his administration to improve the country’s press freedom record.

After a court ordered Zamora to house arrest on May 15, the journalist remains in prison pending two other charges.

Zamora told The Associated Press, “I have to face justice because I can defend myself. … I am innocent.”

As CPJ awaits Zamora’s full release, we have called on “authorities to immediately drop all charges against him” after the journalist was detained for nearly two years in an irregular trial process and sentenced to 6 years in prison.

Such news comes amid a string of cases in which journalists are allowed to go home after arrests yet charges against them remain.

In March, Senegalese authorities released five journalists who have been jailed since last year. At least four of those journalists face ongoing prosecution.

“The release from detention of at least five Senegalese journalists jailed since 2023 is welcome news, but they should have never been arrested, and their cases underscore the imperative for legal reforms to prevent such criminalization of the press in the future,” said Angela Quintal, head of CPJ’s Africa program.

The same month, Congolese journalist Stanis Bujakera Tshiamala was sentenced to six months in prison and a fine but released because he had already served time. His conviction and sentencing sought to justify his detention and sent a chilling message to the press in the DRC that they may face prosecution in connection with their work.

Even when a journalist is released from prison, ongoing threats of persecution can be daunting. CPJ’s Middle East and North Africa Representative Doja Daoud spoke recently with Iraqi Kurdish journalist Guhdar Zebari who was released following three-and-a-half years in detention, including 62 days in solitary confinement. “Every night since my release, my family has been receiving threatening calls from known and unknown individuals,” he told CPJ.

Zebari said he had been swept up in a string of arrests of activists from the ethnic Badinani group who were imprisoned in the wake of 2020 anti-government protests and charged with anti-state crimes.

Repeatedly during elections, protests, and in warzones, authorities are given undue cause to clamp down on journalists. In mid-May, amid the Israel-Gaza war, at least 10 journalists, including three held by Palestinian authorities and seven held by Israel, had been released while 28 remain under arrest. These arrests and releases of journalists are happening in the context of what CPJ has called a growing censorship regime following restrictive measures by Israeli authorities to shutter Al Jazeera and end the live feed from The Associated Press.

Fighting for the release of journalists from behind bars is difficult work. Last year, CPJ welcomed the early release of more than 200 journalists. Far too many, however, face ongoing prosecution. As CPJ works to end the criminalization of journalism, we support these journalists long after they are released as their effort to remain free and to report the news without fear of reprisal continues.

For journalist José Rubén Zamora, and so many like him, that effort isn’t complete until every charge is dropped and a more free and independent press is enshrined into the legal code.