Welcome to the maiden edition of News Public Trust Weekly Column: TIRED WITH THE NOISE?–VIEW FROM THE MIDDLE

National issues, whether political, social, religious, or ethnic, are often framed as contests between two extremes, forgetting the Middle. Yet their real impact is felt across the entire spectrum.

The “Middle” is the eye of the storm, a place of clarity, balance, and pragmatism amid the noise of extremes.

View From the Middle, a weekly column on www.newspublictrust.com between competing narratives.

It avoids ideological heat and focuses on evidence, institutional strength, and pragmatic solutions. It weighs arguments carefully, acknowledging nuance and complexity, and offers balanced, analytical, calm, and measured perspectives.

VIEW FROM THE MIDDLE: National Fula Security of Liberia Saga: Balancing State Authority & Community Protection

By Aurelius Pax

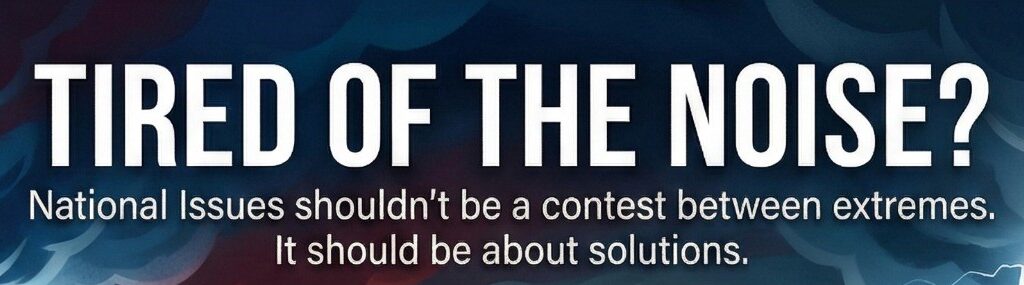

Liberia once again finds itself at a polarizing crossroads. Recent viral images of men drilling in formation under the banner of the National Fula Security of Liberia (NFSL) have ignited a firestorm of public anxiety.

On one side of the divide, critics and government officials see the terrifying specter of an unregulated tribal militia. On the other hand, the Fula community insists the NFSL is a benign, community-based neighborhood watch group designed to protect commercial interests and maintain order during religious gatherings.

In the wake of the controversy surrounding this issue, a profound national anxiety has surfaced regarding the boundaries between community self-defense and state sovereignty.

The Ministry of Justice’s swift order to halt the group’s activities underscored a critical reality: security in a post-conflict Republic cannot operate in a vacuum. To move beyond the polarized rhetoric of rogue militias versus neighborhood watche groups, we must examine the regulatory architecture governing private security in Liberia. This framework is not merely a collection of bureaucratic hurdles; it is the constitutional bedrock that ensures order without sacrificing liberty.

The Social Contract and Constitutional Limit of self-defense

To understand the “NFSL”, we must first look to the Social Contract, championed by philosophers like John Locke and Thomas Hobbes. The foundational premise of any republic is that citizens surrender their individual right to use force, granting the state a monopoly on security. In return, the state promises to protect its citizens’ lives and property.

Philosophically, the concept of regulated private security relies on the delicate balance articulated by the French thinker Montesquieu, who argued that political liberty is found only where power is not abused. To prevent this abuse, systems must be constrained by established laws. When private citizens organize to protect their property, a fundamental right championed by John Locke, they must do so within the structural limits defined by the sovereign state. Without these limits, private protection rapidly devolves into factionalism and vigilantism, as Thomas Hobbes warned would render society chaotic and unstable.

In Liberia, this philosophical balance is codified first and foremost in the 1986 Constitution. Article 80(b) explicitly prohibits any organization from training or equipping a group to use physical force or coercion outside the scope of state authority. It states: “parties or organization which retain, organize, train, or equip any person or group of persons for the use or display of physical force or coercion in promoting any political objective or interest, or arouse reasonable apprehension that they are so organized, trained, or equipped, shall be denied registration, or if registered, shall have their registration revoked.”

To translate this constitutional mandate into everyday governance, the Ministry of Justice, through its Division of Public Safety, maintains strict oversight of the private security sector. In accordance with established national guidelines and regulations, any entity seeking to provide protective services must undergo rigorous government vetting. This process mandates institutional assessments, formal licensing, and strict rules regarding training standards, uniforms, and structural coordination with the Liberia National Police.

However, the efficacy of this ecosystem depends entirely on absolute adherence to the rule of law. The core issue with the NFSL was not the community’s desire for safety, but the apparent circumvention of the Division of Public Safety’s regulatory mechanisms. When a group bypasses legal licensing, operates outside standardized training protocols, and adopts an exclusionary ethnic identifier, it dismantles the accountability that the framework was built to guarantee. Unlicensed groups cannot be monitored for civil rights compliance, nor can they be properly regulated under the national legal frameworks governing detention and the use of force.

Community Vulnerability vs. Regional Threats

However, when state capacity is stretched thin and when police presence is insufficient to manage massive gatherings or deter nighttime burglaries, citizens naturally seek to fill the void.

Recognizing its own manpower limitations, the Liberia National Police established official “Community Watch Forums” (CWFs). These are meant to be unarmed, community-led neighborhood watches that strictly observe and report crimes to the police.

A balanced view requires us to also apply the philosophy of John Locke, who posited that the preservation of property and life is the fundamental reason individuals enter into a society. The organizers of the NFSL have firmly denied any militia ambitions, emphasizing their history of collaborating with the Liberia National Police and their willingness to submit to state oversight. Their underlying need for security is entirely legitimate and rooted in self-preservation.

The Fula community’s desire to organize volunteers to protect mosques and businesses should not be seen as an act of rebellion; it is a predictable human response to a perceived gap in the social contract. Validating this basic need for safety is essential. We cannot ask a community to endure vulnerabilities simply because the state’s umbrella of protection is incomplete.

Yet, while the NFSL’s intent may be benign, its structure and branding are philosophically and practically perilous.

To find the middle ground, we must first look to the philosophical foundations of the modern state. The German sociologist Max Weber famously defined the state as the entity that successfully claims a monopoly on the legitimate use of physical force. Long before him, Thomas Hobbes argued in his seminal work Leviathan that citizens surrender their individual right to use force to a central sovereign to escape the brutish chaos of nature. For a post-conflict nation like Liberia, this monopoly is not merely theoretical; it is the fragile glue holding our hard-won peace together. The emergence of any security apparatus branded along ethnic lines naturally triggers alarms. When security is fractionalized along tribal or religious lines, the state’s foundational authority is inherently undermined.

This apprehension is deeply validated by recent history in the broader West African region. Across the Sahel, in countries like Mali, Burkina Faso, and Nigeria, security lapses in some communities have left vacuums that were rapidly filled by non-state actors. What often began as localized community defense initiatives, such as forest guards or ethnic vigilance committees to protect pastoralists and farmers, frequently devolved into parallel military structures. In the worst scenarios, jihadist factions have exploited these ethnic security divides, using them to recruit, radicalize, and wage insurgency. Liberians observing the regional landscape are not being entirely xenophobic in their fears; they are reacting to a documented pattern where the loss of state security monopolies paves the way for destabilization and extremist violence.

The Danger of Fractionalized Security

When a security apparatus, even an unarmed one, is organized exclusively along tribal lines and adopts a quasi-military structure, it directly challenges the state’s monopoly on force. Security clothed in ethnic identity signals allegiance to a tribe before the Republic. In a post-conflict nation like Liberia, where the scars of factionalism remain tender, parallel security structures breed deep public mistrust. A “National Fula Security” inevitably prompts the question: Who is next? If security becomes a franchised commodity based on tribe, the state’s unifying fabric unravels.

The critical pivot point in this debate lies not in outright condemnation, nor in unquestioning acceptance, but in robust regulatory oversight. The danger lies in the ethnic branding and the parallel structure, not in the concept of private security. While communities have the right to seek lawful protection for their businesses, such entities must be stripped of tribal exclusivity. Security in Liberia must not be compartmentalized as a “Fula,” “Kpelle,” or “Kru” initiative. It must remain unequivocally Liberian.

Safety is a shared responsibility, but national security remains the exclusive domain of the Republic. By shedding its ethnic branding and submitting to the rule of law, the community can protect its people without threatening the nation’s peace.