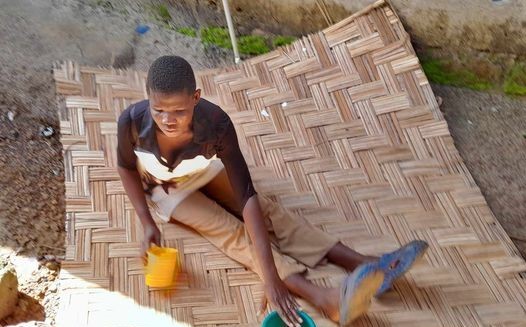

PHOTO: Marpue is looking for water to wash her hands before eating her food

By King Brown with New Narratives

BUCHANAN, Grand Bassa County – Marpue Kpadoe sits on a small bamboo mat and moves her hands around in search of a bowl of water to wash her hands as she prepares to eat. The 18-year-old was born blind. She struggles to take her bowl of potato greens while her sighted peers file past her.

Marpue was once full of hope, dreaming of changing her family’s life through education. Now, as a third-grade dropout, she wonders what will become of her life.

Until she was 13 years old Marpue attended a specialized school for visually impaired students in Margibi County. Her father, a private school teacher, urged her not to let her disability get in her way. She excelled in Braille, a written language where characters are represented by raised dots that are felt by fingertups, and demonstrated a strong desire to learn. Marpue had a bold ambition:

“I want to go to school to be president to help my ma and other blind people,” she says.

But in 2019 Marpue’s father died leaving the family without a breadwinner. Now residing at the Christian Association of the Blind, Marpue shares her daily struggle with 20 other visually impaired children. But the school has no money to education the students. So rather than attend classes, Marpue and her classmates spend their days helping guide older visually impaired people through the streets to beg.

“I feel bad sitting home learning nothing,” says Marpue.

Her mother, Magdalene, 40 and also blind, shares her frustration. “My children’s future is bleak,” she says. “I want them to have a chance at education and a better life, but I cannot provide that for them.”

Marpue’s challenges mirror a national problem facing Liberia’s visually impaired students in rural areas. There is no reliable data for the number of people living with visual impairment in Liberia – Dr. Joseph Kerkula, National Eye Health Program Manager at the Ministry of Health, says new survey data with more accurate numbers will be released this year – but a 2023 World Health Organization report put the number at 35,000.

In rural areas, visually impaired children are stranded. There are just three specialized schools for children with visual impairment in the whole country – with places for fewer than 100 students in total. All three – the Government School of the Blind in Virginia, the United Blind Association in Chicken Soup Factory, and the Christian Association of the Blind National Resource Institute at Via Town R2 Community – are in Montserrado County.

Students who have had access to special support have thrived. Joseph Zarwu, a graduate of Christian Association of the Blind National Resource Institute is now a student at the Adventist University of West Africa. Zarwu is the project coordinator in Liberia for Eric Thunes, an international charity working with children and young people living with visual impairments in Liberia.

“Life is challenging for us, but we must be self-motivated,” says Zarwu. He encourages his peers to focus on education. “Education is sweet. It can transform your life.”

Experts say the crisis of education for Liberia’s visually impaired highlights a national emergency affecting thousands across the country. Without substantial reform and increased funding, the prospects for Liberia’s disabled population remain bleak, perpetuating cycles of poverty and exclusion. Without support, rural students struggle even to raise their own farms and are left with few opportunities other than to beg.

“The plight of visually impaired Liberians is a poignant reminder of our unfinished journey towards inclusivity and equality,” says Sarah Kollie, a disability rights advocate. “We must not be forgotten. Education is our gateway to dignity and opportunity.”

Marpue Kpadoe once dreamed of being president. Without an education her future looks bleak

Grand Bassa County is a good example of the challenges faced by visually impaired children like Marpue. The county had one school dedicated to blind children until 2022. The Grand Bassa School for the Blind operated on a tiny budget of less than $1000 a year with volunteer staff. According to Ipee Dougar, a former principal of the school, the government did not make any payments. Instead, an NGO called the Ivent Foundation, based in Sweden, handled the funding. When the NGO left the country, the organization had no funding to pay the rent.

Once a nurturing environment where 30 students lived on campus and received free education, the school’s closure forced its students to return to the missions or homes they had come from, uprooting their lives and severing the connections they had built.

“The government has failed to support our education adequately. We feel forgotten,” Mr. Dougar says. “I see my students struggle every day. Without proper education, they are relegated to the fringes of society.”

“It saddens me that a large county like Grand Bassa lacks a school for blind children,” says Du-Ben Cleon, a human rights activist, who says that visually impaired people need appropriate services and support to live with dignity. Instead they often face stigma and exclusion, with their needs frequently overlooked in national policies and poverty reduction efforts. “The people here are suffering and are treated as if they don’t deserve to benefit from the country’s resources.”

Experts say that to date almost all support for visually impaired students in Liberia has come from international donors. But many donors are growing weary of donating to Liberia while government officials steal money meant to support their own people. The Boakai government is facing increased pressure to deliver public services itself.

Robert Kpadoe, head of the Christian Association of the Blind, criticizes successive governments for their failure to prioritize disability rights. Kpadoe points to chronic underfunding and misallocation of resources as major issues undermining efforts to support disabled individuals.

“Government promises have amounted to little more than lip service,” Mr. Kpadoe says.

The new Boakai government promises that it is listening. In a telephone interview, Samuel Dean, the new Director of the National Commission on Disabilities (NDC), said he could not provide detailed information on how much is allocated to support blind students while he is still restructuring his administration. But he said educational resources for visually impaired students was a priority.

“The lack of schools is a major issue,” Mr. Dean said.

Disability activists will be watching closely. Daintowon Domah Pay-Bayee, former chairperson of Liberia’s National Commission on Disabilities under the Weah administration, says she struggled to have the administration devote significant funds to the issue.

“When I took over the NDC, I inherited a budget of $100,000 USD,” Madam Pay-Bayee says. “We lobbied with the government at the time, and our budget increased from $100,000 to $700,000. We used those funds to send people with disabilities to private universities and schools, and to provide food and other resources for our community.”

But the 2024 budget allocation for the NCD has dropped to just around US$200,000 from $500,000 in 2023. Madam Pay-Bayee says even at its highest level funding is grossly inadequate to meet the needs of Liberia’s estimated 900,000 people living with disabilities. Pay-Bayee advocates for a comprehensive National Action Plan aligned with the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities, focusing on six critical areas: access to public services, education, health, employment, independent living, and justice.

For now, students like Marpue are struggling for day-to-day survival with little hope of breaking free in the future.

This story was a collaboration with New Narratives. Funding was provided by the American Jewish World Service. The funder had no say in the story’s content.